‘One of the most hated men in Winnipeg’: Trial sees letters from serial killer

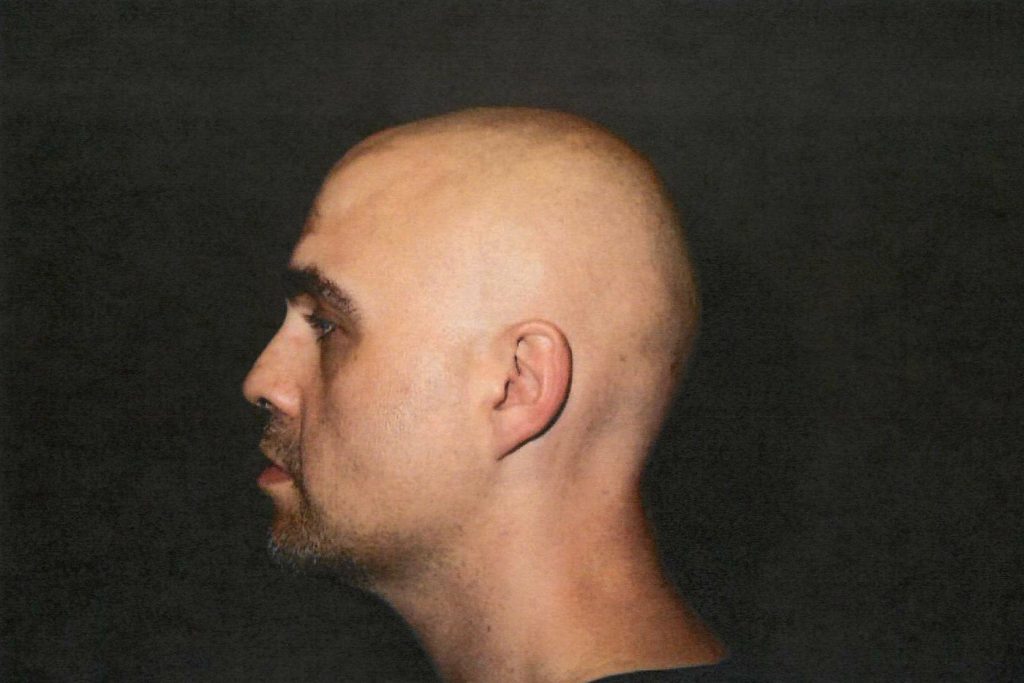

WINNIPEG — The trial of admitted serial killer Jeremy Skibicki learned about him through his own words Wednesday, with pen pal letters in which he discusses everything from the persecution of Caucasians to his post-apocalyptic zombie novel.

“A racist is someone who wakes up white in the morning,” Skibicki wrote to a fellow inmate in a series of letters entered into evidence at his trial.

The letters, from over a year ago, also foreshadow Skibicki’s legal strategy and how he thinks he should not be held criminally responsible because of mental illness.

Advertisement

Skibicki, 37, is on trial charged with first-degree murder in the deaths of four Indigenous women in 2022.

The trial was originally to be heard by a jury. But both sides agreed to a judge-alone trial just before it began, when defence lawyers announced Skibicki admits to killing the women but should be found not criminally responsible.

The Crown has presented video, DNA, computer and witness evidence linking Skibicki to the victims to illustrate possible planning and coverup of the crimes.

On Wednesday, the Crown wrapped up its case by entering into evidence nine letters Skibicki wrote over four months early last year to a woman in a Nova Scotia correctional facility as part of a pen pal program.

In the letters, Skibicki acknowledges his words will be monitored and read by officials. In one, he says he can’t say much about his case but adds, “I am seriously considering giving up even though I have a Not Criminally Responsible defence with experts.”

Advertisement

In another letter, he laments being held in segregation due to public attention in his case.

“I’m probably one of the most hated men in Winnipeg (if not all of Canada),” he writes.

“It’s refreshing to have a real connection with someone who is not judgmental.”

The letters detail other thoughts and sentiments.

Skibicki writes that he was born in Winnipeg and adopted by a Polish family. His birth mother is from Newfoundland and he has a half-sister who still lives there.

Advertisement

He likes online video games, playing guitar and cooking. He listens to metal, electronica, classical music and Gregorian chants.

In one letter, he writes a prologue to a zombie novel set in Winnipeg during the collapse of society amid world war. He wonders if he can still profit from the sale of a work of fiction not linked to his criminal case.

He bemoans the possibility of a jury trial, writing: “The majority of people in this country are liars and self-serving. The jury will absolutely be biased.”

He asks his pen pal to call him Anton, saying he prefers that name over his given name. Court previously heard Skibicki had multiple Facebook accounts linked to a variation of that name where he posted religious scripture and white supremacy ideology.

Also in the letters, Skibicki dismisses the impact of sexual abuse in residential schools and links other religions to child abuse. But he says, “We’re not allowed to talk about that (and we’re racist bigots if we do).”

Advertisement

Skibicki is charged in the deaths of Rebecca Contois, 24; Morgan Harris, 39; Marcedes Myran, 26; and an unidentified woman Indigenous leaders have named Mashkode Bizhiki’ikwe, or Buffalo Woman.

Crown prosecutors have said the killings were racially motivated and Skibicki preyed on the vulnerable victims at homeless shelters.

The trial has heard Skibicki assaulted his victims, strangled or drowned them and disposed of their bodies in garbage bins in his neighbourhood. Myran and Contois were dismembered.

The trial resumes June 3, when the defence is expected to call an expert to testify about Skibicki’s state of mind at the time of the killings.

The federal government has a support line for those affected by the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls: 1-844-413-6649. The Hope for Wellness Helpline, with support in Cree, Ojibway and Inuktitut, is also available to all Indigenous people in Canada: 1-855-242-3310.

Advertisement

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 22, 2024.

Brittany Hobson, The Canadian Press